Posts Tagged ‘Jeff Moran’

UN ATT: REACHING FOR RESET?

Tuesday, November 6th, 2012New Coalition Says Current Draft Arms Trade Treaty Would Be Worse For Humanity

By Jeff MORAN | Geneva

An informal coalition of prominent academics, researchers, and advocates in the fields of international human rights law and small arms control policy-making condemned the 26 July 2012 draft United Nations (UN) Arms Trade treaty (ATT) on 30 October. [1]

According to statements made, the draft ATT is absolutely unacceptable and adopting it without substantial changes would be worse for humanity than if there was no ATT at all. They expressed their position during a news briefing at the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, where they discussed the publication of “Academy Briefing #2: The Draft Arms Trade Treaty.” [2]

The formal official authors of the publication were Dr. Stuart Casey-Maslen, a Research Fellow at the Geneva Academy, and Ms. Sarah Parker, a Senior Researcher at the Small Arms Survey. The authors coordinated with and received input from representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Saferworld, and Oxfam. [4]

This is a significant development in humanitarian advocacy designed to influence the unfinished UN ATT negotiations process, which is expected to formally re-open where it left off and run for 10 days under consensus rules from 18-28 March 2013. [3] The condemnation may embolden states aligned with Mexico to kill consensus and to take the ATT negotiations outside the UN. This would amount to hitting the reset button and clearing the way for a more controversial treaty to be adopted under less rigorous two-thirds majority rules. [5]

Dr. Stuart Casey-Maslen was unable to be present for the news briefing due to a family emergency and so was unavailable for comment. Dr. Casey-Maslen was a member of the Swiss delegation to the ATT negotiations. He was also on the ICRC delegation to the Oslo Diplomatic Conference in 1997 that adopted the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, which was a treaty that was developed outside the UN system and championed mainly by non-governmental organizations.

Ms. Sarah Parker sat in Dr. Casey-Maslen’s place and has been a member of the Australian delegation during the UN ATT process. Ms. Parker was joined by Mr. Gilles Giacca who is a researcher and Ph.D. candidate at the Geneva Academy. The news briefing was led by Dr. Andrew Clapham, co-Director of the Geneva Academy and author of several books on international humanitarian law.

News Briefing Details

Dr. Clapham opened the news briefing, and then passed the floor to Mr. Gilles Giacca who spoke for about six minutes. This was followed by Dr. Clapham again for about 15 minutes. This left over 30 minutes for a lengthy question and answer session where nine questions were answered. The briefing was attended by over 100 people. One professional reporter self-identified and asked the first question at the end.

Mr. Gilles Giacca first provided some historical context and motivations for the ATT. He then listed international instruments and declarations designed to increase controls over small arms and light weapons, to reduce arms related violence worldwide:

1. UN Program of Action on Small Arms,

2. UN Firearms Protocol,

3. The UN International Tracing Instrument, and the

4. Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development.

Then he discussed the main challenges for the negotiations of the ATT so far:

1. Defining the scope of the weapons to be regulated by the ATT.

2. Defining the criteria to be used to condition authorized international transfers of weapons subject to the ATT.

3. Defining the monitoring, compliance, reporting and implementation mechanisms of the ATT, for such things as the provision of victim assistance.

4. The US insisting on negotiating by consensus rules, and so creating the option for a single country to “spoil” the treaty.

5. The large gap between two main camps: those who want a narrow scope treaty, and those who want a broad scope treaty.

After Mr. Giacca concluded, Dr. Andrew Clapham opened his comments by stating that the ATT should be an instrument “to prevent arms from fueling human rights violations or violating international humanitarian law.” He went on to state “what’s at stake here, I think, is that the treaty has a number of flaws or loopholes in it. And if it were going to be adopted in current form, arguably it could be worse than no treaty.”

Dr. Clapham said further that in various places the ATT appeared to set the bar lower than existing international standards, and that this would amount to a step backwards, or a “retrogression in international standards” as is stated in the Academy Briefing. [6]

He then detailed his main problems with the draft ATT, though he elaborated many problems as discussion developed into the question and answer period. His short-hand for three main problems were: 1) the complicity problem, 2) definition of war crimes, and 3) the balancing problem.

1. Complicity Problem. This criticism focused on Article 3, paragraph 3 and specifically cited the text “A State Party shall not authorize a transfer of conventional weapons within the scope of this Treaty for the purposes of facilitating the commission of genocide, crime against humanity…” Here Dr. Clapham stated that the “for the purposes of facilitating” is too high a standard and is essentially not in line with international customary law. He said there should be an awareness test or a knowledge test, but not a purpose test. [7]

2. Definition of War Crimes. This criticism focused on Article 3, paragraph 3. In short he stated that limiting war crimes to “grave breaches” of the 1949 Geneva Conventions or serious violations of Common Article 3 of those Conventions would exclude most violations that are thought to be occurring in Syria, violations such as the disproportionate targeting of civilians. [8]

3. The Balancing Problem. This criticism focused on Article 4, paragraph 5. His basic point was that the use of the term “overriding” implied a balancing of peace and security v. human rights violations. He further stated that that if the “overriding” language was kept in the treaty, and if the common understanding by diplomats was that there should be a balancing of peace and security v. human rights violations, this would be “a step backwards” because “it takes away the idea that human rights are something absolute, that there can be no violations under any circumstances.” He suggested using other words such as “substantial risk,” “clear risk,” or even “overwhelming risk.” [9]

Other issues Dr. Clapham addressed in passing were:

4. The treaty scope (e.g. the exclusion of tear gas and rubber bullets for example).

5. Ambiguity about the definition for ammunition, munitions.

6. Ambiguity about the definition of trade (e.g. does it include state gifts and loans?)

Observations & Other Discussions

Most of the discussion was about loopholes and weak ATT language with respect to promoting human rights. The news briefing seemed at times, however, to be a public lamentation with the United States essentially blamed first for insisting upon consensus rules at the outset of the negotiations process in 2009, and then spoiling the draft treaty by creating the “balancing problem” between human rights and state security. [10]

While Dr. Clapham acknowledged the ATT as a “trade” and “export” treaty at one point, his commentary was delivered as if the treaty was designed purely to serve as an instrument of global civil society improvement, one that is too important to be frustrated in any way by others concerned about national sovereignty, security, and business interests, and/or the principle of individual right to armed self-defense.

The speakers were clearly frustrated with the draft ATT, and the negotiations process to date. It was not clear if this was indicative of just a distaste for the messy multilateral reality of accommodating diverse state interests, an acquired disdain for those diplomats and delegations guided more by how the world is rather than how the world should be, or both.

Yet the mood was not entirely down. The room became guardedly positive when talk turned to the taking the ATT negotiation process outside the UN, to “do it right” as Mr. Giacca said on the Geneva Academy ATT Legal Blog post that was projected onto the wall behind the stage during the news briefing. [11] This discussion thread developed in response to a question about the probability of Mexico, for example, leading a push to take the ATT outside the UN.

In response to this question, Dr. Clapham reframed the ATT as a once in a lifetime opportunity to save humanity from rights abuses, and implied that he and others like Dr. Keith Krause (the Founding Director of the Small Arms Survey, also seated in the audience) were hoping to get a good ATT done “on their watch.”

But Dr. Clapham acknowledged a certain level of fatigue may set in and that diplomats and some humanitarian groups might just settle for a lowest common denominator to get the ATT done. He went on to state however that “there’s a good chance, that if people realize they are going to get something which is worse than nothing…and if the Mexican leadership…has the stomach for this, it could get taken outside the UN.” He went on to say this would allow for an ATT text to be approved “with only a two-thirds majority and we’d arguably get a much better text.” Sarah Parker, and Gilles Giacco also commented on this situation as well.

The discussion got pessimistic again when Dr. Krause actually took the floor to make comments about Article 4 and the national assessment provisions. He essentially declared that the draft ATT, without fundamental changes, could result in a “pretty instrument that actually doesn’t change anything that actually happens in the world.” The reasoning being that weapons transfers would be subject to national assessment without any meaningful way for non-governmental organizations and other states to legally challenge a State’s own assessment process and decisions to export/transfer arms abroad, and this, in his words, would be “tragic.” Dr. Krause seemed to offer that another good reason to take the ATT outside the UN system would be for “limiting the scope of malicious interpretation” of the ATT by state parties.

Sarah Parker, who works for Mr. Krause at the Small Arms Survey, then explained how provisions for increased accountability and transparency on national assessment could be added through an implemented “ATT system” when the “political climate” was better, eventually, after countries become “more comfortable” with the ATT’s obligations. She elaborated that a State’s own national assessment decisions could be made subject to legal challenges in international courts.

Dr. Clapham even suggested how reports from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch could eventually precipitate court-ordered injunctions halting government arms exports / transfers provided that campaigners and advocates first help bring about appropriate controlling national legislation. Dr. Clapham and Ms. Parker were presumably referring to more politically open states only, and the United States especially.

At the end, Ms. Parker importantly clarified that the ATT is not about creating a new tier of illegal transfers. Rather, “the ATT is introducing a new tier which is where [some] arms transfers are considered irresponsible, and therefore illegal.”

Looking Forward

Dr. Clapham, Mr. Giacca, Dr. Krause, and all seemed hopeful for an ATT negotiated outside the UN system (i.e. without consensus rules, with fewer countries required for an ATT to enter into force, with higher standards, broader scope, better text overall etc). [12] Ironically for them and like-minded partners at the ICRC, Oxfam, and Saferworld, realizing these hopes now seems best assured if nations don’t reach consensus at the UN ATT Conference in March.

Will humanitarian rights groups and sympathetic state delegations help move the UN ATT Conference talks forward by consensus, or will they act to kill consensus themselves?

Deliberately killing consensus will hit the ATT reset button and would be hypocritical at the very least, particularly since such groups were the first to accuse the United States and others of doing this in July. [13] Regardless of who might kill consensus in March, doing so will certainly lead to further institutional division within the international system. With Syria now in a full civil war, and the risks of major regional conflict accelerating, more division seems the last thing the world now needs.

Indexed Audio

The downloadable audio for this conference is just under 53 minutes and 7MB. It is complete except for the first few minutes of introductions. The only edits made to the audio file were to enhance voice and minimize noise. This said, there are some points where noise may make it difficult to clearly understand speakers. You can download it here.

00:00 – 05:47 | Presentation by Gilles Giacca

05:48 – 20:18 | Presentation by Dr. Andrew Clapham

20:19 – 21:04 | Question 1 and response (on the United States creating the “balancing problem”)

21:05 – 24:13 | Question 2 and response (on violence against women provisions)

24:14 – 26:41 | Question 3 and response (on implications for private military companies)

24:42 – 27:37 | Question 4 and response (on conflicts between an ATT and international law)

27:38 – 33:13 | Question 5 and responses (on taking the ATT outside the UN system)

33:14 – 34:25 | Question 6 and responses (on individual and business applicability)

34:26 – 36:15 | Question 7 and comment by Keith Krause (on national assessments)

36:16 – 39:09 | Dr. Clapham response to Keith Krause (on national assessments)

39:10 – 41:02 | Sarah Parker comments to Keith Krause (on national assessments)

41:03 – 42:08 | Dr. Clapham second response to Keith Krause (on national assessments)

42:09 – 44:43 | Question 8 and responses (on the definition of authorization)

44:44 – 52:06 | Question 9 and responses (on legitimating the arms trade and exporting to third parties)

52:07 – 52:51 | Dr. Clapham clarification about transfers to third parties, and close)

About The Author

Jeff Moran, a Principal at TSM Worldwide LLC, specializes in the international defense, security, and firearms industries. Previously Mr. Moran was a strategic marketing leader for a multi-billion dollar unit of a public defense & aerospace company, a military diplomat, and a nationally ranked competitive rifle shooter. He is currently studying international law of armed conflict with the Executive LL.M. Program of the Geneva Academy. Earlier this year he completed an Executive Master in International Negotiation from the Graduate Institute of Geneva. Mr. Moran also has an MBA from Emory University’s Goizueta Business School and a BSFS from Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service.

End Notes

[1] The first session of the UN ATT Conference was held from 3 -28 July and ended with no action on the final draft treaty dated 26 July 2012. A .pdf version of this draft ATT is available here.

[2] The Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights website is here. According to the back of the briefing cover, the Geneva Academy “provides post-graduate teaching, conducts academic legal research, undertakes policy studies, and organizes training courses and expert meetings;” and “concentrates on the branches of international law applicable in times of armed conflict.” A .pdf of the Academy Briefing is available in here.

[3] A draft resolution before the First Committee of the United Nations is available at here.

[4] The stated authors of the briefing acknowledge collaboration from Roy Isbister, Claire Mortimer, and Nathalie Weizmann on the front inside cover of the Academy Briefing. These individuals are well-known representatives of Saferworld, Oxfam, and the ICRC respectively. While a disclaimer states the views expressed “do not necessarily reflect those of the project’s supporters or of anyone who provided input to, or commented on, an earlier draft,” previous public statements by these individuals indicate strong concurrence with the briefing by these individuals and their respective employers. You can learn more about the Small Arms Survey here.

[5] Mexico is most likely to lead the effort to reset the ATT negotiations outside the United Nations based on its prior statements and actions during ATT negotiations process since 2009. At the conclusion of the UN ATT Conference in July, they spoke on behalf of 90 countries signaling a clear willingness represent the interests of other like-minded states. A .pdf of this statement is available here.

[6] “Academy Briefing No. 2: The Draft Arms Trade Treaty.” Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights. 30 October 2012. Page 31.

[7] Ibid., page 23.

[8] Ibid., page 23.

[9] Ibid., page 25.

[10] Mr. Giacca made reference to the problem of consensus rules and the US insistence on them in his remarks. A .pdf of the press statement announcing the US support for the ATT negotiations with consensus rules is available here. Dr. Clapham specifically identified the US as creating the balancing problem when answering the first question from the audience. You can hear this starting at 20 minutes and 19 seconds in the audio file referenced above.

[11] A .pdf of the blog post presented during the news briefing is available here.

[12] Among the people making comments at the news briefing, Ms. Parker was alone in declaring her preference for a treaty by consensus through the UN system.

[13] Here are links to press releases from Reuters, Oxfam, Amnesty International, and Control Arms. Sources last accessed 5 November 2012.

First Published: 5 November 2012

Last Updated: 5 November 2012

Online republication and redistribution are authorized when this entire publication (including byline, hyper-links, and Indexed Audio, About the Author and End Note sections) and linkable URL http://tsmworldwide.com/reaching-for-reset/ are included.

How the 2012 UN Arms Trade Treaty Conference Really Died

Thursday, October 18th, 2012(H/T Jeff Moran, TSM Worldwide)

By Jeff Moran | Geneva

Advocacy and diplomatic discussions started again last week with the opening day of the UN General Assembly First Committee meetings.[1] These meetings end on 6 November 2012 (Election Day in the United States), and follow-up the failed United Nations (UN) Conference in July to formally negotiate by consensus a legally binding Arms Trade Treaty (ATT).[2]

Contrary to prevailing reportage and opinion, the UN ATT Conference was less a failure in diplomacy, or a victory by the firearms industry and the National Rifle Association for that matter, than it was the result of abortive advocacy lead by the UK-based Control Arms campaign and its unrealistically expansive vision for a more extreme trade treaty than consensus could sustain.[3]

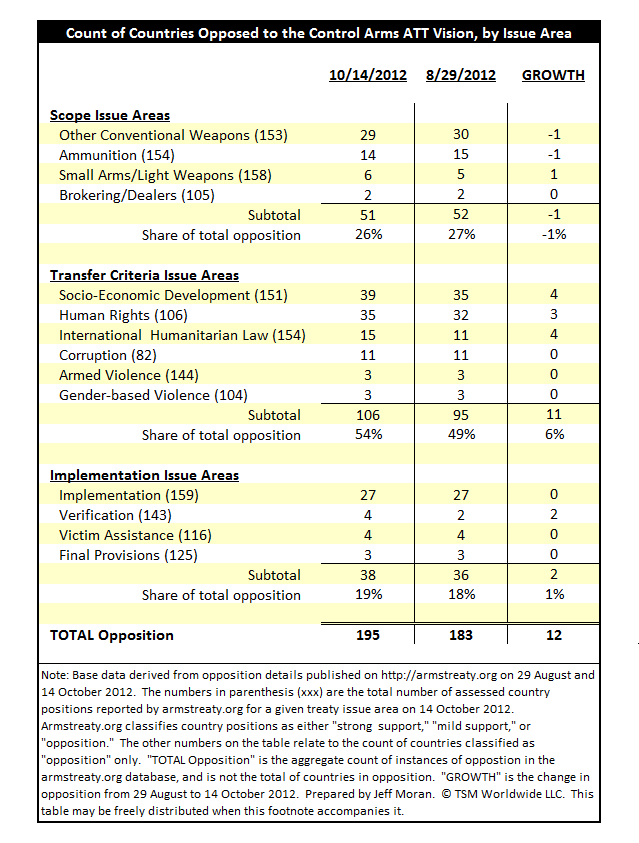

The Control Arms vision for the ATT encompasses 14 specific treaty issue areas under three categories: Scope, Transfer Criteria, and Implementation. Scope issues areas include Ammunition, Brokering/Dealers, Other Conventional Weapons, and Small Arms/Light Weapons. Transfer Criteria issue areas include Armed Violence, Corruption, Gender-based Violence, Human Rights, International Humanitarian Law, and Socio-Economic Development. Implementation issue areas include Final Provisions, Implementation, Verification, and Victim Assistance.

The Control Arms vision across these treaty issue areas can be found on their subsidiary armstreaty.org website.[4] The details of their ATT vision are quoted below:

1. Ammunition. Including in the scope of the ATT all “ammunition, munitions, and explosives.”

2. Brokering/Dealers. Including in the scope of the ATT brokering and dealing. “Brokering generally refers to arranging or mediating arms deals and buying or selling arms on one’s own account or for others, as well as organizing services such as transportation, insurance or financing related to arms transfers, and the actual provision of such services.”

3. Other Conventional Weapons. Including in the scope of the ATT “all conventional weapons, related components and production equipment, beyond Small Arms and Ammunition” which are “covered by the 7 categories in UN Register of Conventional Arms and of other conventional weapons, components and equipment.”

4. Small Arms/Light Weapons. Including in the scope of the ATT “conventional weapons that can be carried by an individual or a group of individuals (including revolvers, machine guns, hand-held grenade launchers; portable anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns and missile systems; and mortars of calibers less than 100 mm. etc).”

5. Armed Violence. Including as a parameter of the ATT “provisions to restrict transfers that could provoke, fuel or exacerbate armed conflict and armed violence.”

6. Corruption. Including as a parameter of the ATT “provisions to restrict transfers that could exacerbate or institutionalize ‘corruption’ or ‘corrupt practices’. In the context of arms transfers, corrupt practices include bribing of state officials with commissions and kickbacks provided by arms producers and traders to facilitate a transfer agreement.”

7. Gender-based Violence. Including as a parameter of the ATT provisions to “restrict the transfer of arms where there is a substantial risk that the arms under consideration will be used to perpetuate or facilitate acts of gender-based violence, including sexual violence.”

8. Human Rights. Including as a parameter of the ATT “provisions to restrict transfers when there is substantial risk that the arms will be used in serious violations of international human rights law, including fueling persistent, grave or systematic violations or patterns of abuse.”

9. International Humanitarian Law. Including as a parameter of the ATT “provisions to restrict transfers when there is substantial risk of the arms being used in serious violations of international humanitarian law (IHL). This assessment would include consideration of whether a recipient that is, or has been, engaged in an armed conflict has committed serious violations of IHL or has taken measures to prevent violations of IHL, including punishing those responsible.”

10. Socio-Economic Development. Including as a parameter of the ATT “provisions to restrict transfers that could hinder, undermine or adversely affect socio-economic development.”

11. Final Provisions. Including in the text of the ATT “effective implementation mechanisms of the Arms Trade Treaty, including criminalization of treaty violations and an Implementation Support Unit (ISU) to coordinate international cooperation.”

12. Implementation. Including in the text of the ATT final provisions and entry into force mechanisms. “Effective final provisions would not allow reservations that would be incompatible with the Treaty’s purpose. Effective entry into force mechanisms would not include a requirement for excessive number of ratifications, nor for specific states or groups of states to ratify the treaty, before it could enter into force.”

13. Verification. Including in the text of the ATT “effective verification mechanisms of the Arms Trade Treaty. Effective verification includes meaningful and specific annual reporting, external referral for dispute resolution, annual meetings of states party (MSP) and five-yearly Treaty Review Conferences (RevCons), and the creation of an Implementation Support Unit (ISU) to assist with, collect and analyze reports.”

14. Victim Assistance. Including in the text of the ATT “the recognition of the rights of victims of armed violence and acknowledgment of States’ commitment to provide assistance to victims.”

Reaching consensus during the UN ATT Conference was certainly possible, and potentially a constructive endeavor for all nations from an interest point of view. But consensus was not likely because a lot of countries thought aspects of the emerging ATT were potentially threatening to national sovereignty for example.[5] Nonetheless, the popular narrative is that the United States killed the Conference when it asked for more time to consider the draft treaty on the final day of the Conference.[6] This expedient and seemingly anti-American explanation doesn’t stand up to scrutiny, especially when you put the Conference into context and examine the armstreaty.org database about opposition to the ATT.

The relevant historical context for what happened at the Conference extends back to at least the creation of the International Action Network On Small Arms (IANSA) in 1999. Important context also includes the recorded debate between the leaders of IANSA and the National Rifle Association in 2004 along with several formal rounds of preparatory negotiations since 2009 for example. This is admittedly a lot of history for one to casually consider, but after surveying this period, and listening to diplomats based in Geneva, a pattern of overdone, unfocussed, and ultimately counterproductive advocacy emerges. This appears to be due, at least in part, to self-inflicted wounds from years of overselling positions and distractive issue framing, which, in turn, appears to have damaged their credibility and cause.[7] Ultimately, humanitarian groups, led by an unraveling Control Arms coalition, sabotaged consensus for an ATT by pushing diplomats too hard for far too much and provoked dispositive sovereignty concerns across the Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East in addition to the United States.[8]

Not only was there no consensus on the final draft ATT as a whole in those final days of the Conference, but there remains no consensus for any of the 14 treaty elements Control Arms continues to advocate for, and opposition to them is growing. This can be evidenced in detail on armstreaty.org.[9] While the data on armstreaty.org are not an official record of country delegation viewpoints during the final days of the ATT conference, they serve as a useful proxy indicating size, scope, and direction of opposition to the ATT as Control Arms envisions it.

Clearly, the most widely opposed ATT issue areas fall under the creation of transfer conditionality / restrictive criteria on the international transfers of arms. The most objected-to transfer criteria remain those related to Socio-Economic Development and Human Rights. Thirty-nine and 35 countries oppose these criteria respectively, the US not being among them. The US opposed only three provisions cutting across treaty scope and implementation issue areas only.[10]

The accompanying table below is made from armstreaty.org data and evidences the above points. It also conveys more important details about the lack of consensus for an ATT. The table indicates, from a treaty content point of view, where opposition is greatest, the relative size of the opposition, and the direction of opposition since the Conference. [11]

In short, the table below helps show why the assertion that the US is mainly responsible for killing consensus at the UN ATT Conference is not only false, but absurd. Here are nine take-aways:

1. There are 195 total instances where a country opposes an aspect of the envisioned ATT (consensus requires zero instances or at least a willingness to no longer publicly oppose, and Control Arms attributes just 3 of these 195 to the US).

2. There is no consensus for any of the provisions across the all three treaty issue area categories (Scope, Transfer Criteria, and Implementation).

3. Total opposition to the Control Arms vision has actually grown in the months after the UN ATT Conference (by 12 net instances, or 7%).

4. There is a two-way tie for issue areas experiencing the fastest opposition growth: Socio- Economic Development and International Humanitarian Law (both together account for 2/3 of the growth in total opposition).

5. The most-opposed category of treaty issue area is Transfer Criteria (54% share of total opposition) and opposition has grown (by 11 instances, or 6%, since 29 August 2012).

6. The most-opposed treaty issue area by country count is Socio-Economic Development (39 countries opposed).

7. The most-opposed issue area by percentage of countries opposed (relative to total number of countries assessed) is Human Rights (33%).

8. The least-opposed provision by country count relates to including the activities of arms Brokering/Dealing within the scope of the ATT (2 countries opposed).

9. There is a three-way tie for the least opposed provisions by percentage of countries opposed (relative to total number of countries assessed): Brokering/Dealers, Armed Violence, and Final Provisions (all at 2% opposed).

Rightly understood, Control Arms’ own data help to correct the false narrative about why the UN ATT Conference failed to reach consensus this summer. Such data clearly show that the prospects for consensus were grim at best, and are getting worse. The data also suggest that even if the US enthusiastically embraced the final draft ATT, other countries would have probably worked together to prevent consensus anyway.

It is not a giant leap in logic to see that Cuba, Iran, or Venezuela (countries that each oppose many more treaty provisions than the US does) probably would have killed consensus themselves, especially if the United States indicated it was going to sign the treaty. Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, for one, faced an election within months. Being the consensus breaker would have surely boosted President Chavez’ domestic political standing, and perhaps his image as a regional guardian against outside meddling.

In conclusion, UN ATT Conference died from lack of consensus. This death was due less to failed diplomacy, or pressure by the firearms industry and gun rights groups, than it was the result of many years of abortive advocacy lead by an unraveling UK-based Control Arms campaign. Control Arms’ broad vision for the ATT was more extreme than consensus could sustain. Ultimately, humanitarian groups sabotaged consensus for an ATT by pushing diplomats too hard for far too much and provoked dispositive sovereignty concerns across the Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East in addition to the United States.

Perhaps a more extreme version of the ATT will be born outside the UN altogether. If this happens, it would likely share a destiny not unlike like the 1997 Ottawa Treaty banning anti-personnel landmines. Ottawa was born outside the UN because an anti-personal mine ban did not get traction inside it. Russia, China, and the United States have still not ratified or acceded to the treaty. And while 33 other states have not ratified or acceded to the Ottawa Treaty either, supporters argue that the treaty is emerging as an international norm on its way to acquiring the force of international law over time.[12]

Most likely, within a year, the UK, the lead country responsible for putting the ATT on the UN agenda in 2006, will introduce the draft ATT to the UN General Assembly and seek signatures from countries willing to sign it as is. Unfortunately, regardless of what course the ATT takes, moving forward with an ATT not based on consensus will only serve to divide the international community. As the specter of major conflict looms larger over volatile regions of the world, more division is now the last thing the international community needs.

About The Author

Jeff Moran, a Principal at TSM Worldwide LLC, specializes in the international defense, security, and firearms industries. Previously Mr. Moran was a strategic marketing leader for a multi-billion dollar unit of a public defense & aerospace company, a military diplomat, and a nationally ranked competitive rifle shooter. He is currently studying international law of armed conflict with the Executive LL.M. Program of the Geneva Academy. Earlier this year he completed an Executive Master in International Negotiation from the Graduate Institute of Geneva. Mr. Moran also has an MBA from Emory University’s Goizueta Business School and a BSFS from Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service.

End Notes

[1] The First Committee “deals with disarmament, global challenges and threats to peace that affect the international community and seeks out solutions to the challenges in the international security regime.” It meets in October each year. See http://www.un.org/en/ga/first/ for more information about this. Opening day official statements can be found at http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2012/gadis3453.doc.htm. Oxfam International has a blog associated with this series of meetings at http://blogs.oxfam.org/en/blogs/12-10-12-fighting-arms-trade-treaty-un-general-assembly. All links last accessed 15 October 2012.

[2] The key deliverable from the UN ATT Conference was an unsigned final draft treaty dated 26 July 2012. This draft is available at http://www.un.org/disarmament/convarms/ATTPrepCom/Documents/PrepCom4%20 Documents/PrepCom%20Report_E_20120307.pdf. Last accessed 14 October 2012.

[3] The Control Arms Campaign is the flagship civil society campaign advocating for an ATT. It started-up in 2003 as a powerful collaboration among the UK offices of Amnesty International, the International Action Network on Small Arms (IANSA), and Oxfam International. In addition to having been funded by a few governments, Control Arms has support from under a 100 mostly Western advocacy groups yet views itself as a “global civil society alliance.” There are many different humanitarian groups and campaigns, but Control Arms is the biggest. Another campaign, the Campaign Against the Arms Trade, is loud and vocal, but is not taken seriously by governments because it advocates for a total ban on the Arms Trade.

[4] Armstreaty.org is the leading ATT negotiations tracking website created by the Control Arms campaign and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. http://armstreaty.org/mapsstates.php. Last accessed 15 October 2012.

[5] Such views underpin many official views found the May 2012 official UN document “Compilation of Views on the Elements of an Arms Trade Treaty (A/CONF.217/2.” http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/CONF.217/2. Last accessed 15 October 2012.

[6] Here are links to press releases from Reuters, Oxfam, Amnesty International, and Control Arms: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/27/us-arms-treaty-idUSBRE86Q1MW20120727, http://www.oxfam.org/en/pressroom/pressrelease/2012-07-28/battle-arms-trade-treaty-continues-governments-opt-delay-final-dea, http://amnesty.org/en/news/world-powers-delay-landmark-arms-trade-deal-2012-07-27, and http://www.controlarms.org/battle-continues. Sources last accessed 14 October 2012.

[7] Author conducted interviews with numerous diplomats and country delegates in and around the Geneva-based UN disarmament community in 2012. A consistent portrait painted by them was that Control Arms campaigners exhibited a profound lack of collective unity and focus, and that messaging was redundant, superficial, grossly insufficient to help in a technical or practical sense, and largely amounted to a waste of time even for diplomats and delegates who were sympathetic to their cause. Additionally, Control Arms Campaigners undermined their own efforts by insisting on adding controversial provisions to the treaty, such as Victim Assistance, which made consensus all the more unattainable.

[8] Control Arms is described as “unraveling” because, by 2012, Control Arms had essentially disintegrated as a cohesive coalition. This appears to be a key reason for a lack of focus in campaign execution. The proximate cause for this appears to be a case of disintegration due to interpersonal problems and hubris among its leaders, and organizational self-interest. Amnesty International essentially left Control Arms to pursue its own agenda in 2011. This information was corroborated by interviews with several diplomats and an interview with a professional arms trade researcher with direct knowledge of the situation and people concerned, May 2012.

[9] TSM Worldwide LLC conducted a comparative analysis of the website using snapshots taken 29 August and 14 October 2012.

[10] The only Scope issue area the US objected to was the inclusion of ammunition in the treaty. The implementation issue areas the US objects to are Final Provisions and Victim Assistance. Source: armstreaty.org. Last accessed 14 October 2012.

[11] The graphic represents outright country opposition to given issue areas as gauged by Control Arms only. The totals at the bottom of the table are counts of distinct instances of country / issue-area opposition and do not reflect the count of countries opposed to the ATT as a whole.

[12] One group is Handicap International, sponsors of the Campaign to Ban Landmines and co-winner of the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize. http://en.handicap-international.ca/Ottawa-treaty-good-news-and-bad-news_a186.html Last accessed 1 October 2012.

First Published: 17 October 2012

Last Updated: 18 October 2012

Republication and redistribution are authorized when author Jeff Moran and linkable URL http://tsmworldwide.com/consensus-killed/ are cited.

In case you missed it: Dishonest Humanitarianism

Monday, July 9th, 2012In case you missed it, the article Jeff Moran of TSM Worldwide published on TheGunMag.com and IAPCAR.org was featured in an AmmoLand.com blog article.

DISHONEST HUMANITARIANISM? The invalid assumptions behind the United Nations’ small arms control initiatives

Thursday, June 14th, 2012DISHONEST HUMANITARIANISM? The invalid assumptions behind the United Nations’ small arms control initiative

By Jeff Moran

Next month diplomats from the world over will converge at the United Nations in New York to formally negotiate a legally binding Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). This is the culmination of over a decade of humanitarian advocacy and pre‐negotiations inside and outside the United Nations. It’s part of a larger global effort kick‐started in 2001 with the passage of a non‐legally binding resolution by the UN General Assembly. This resolution was called the “Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All Its Aspects” (PoA).(1) This led to the creation of many initiatives, the most visible and contentious of which has been the ATT.

The ATT process formally got underway with two subsequent UN resolutions lead by the United Kingdom and is still Chaired by Argentine Ambassador Roberto Moritán. In 2006, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 61/89 entitled “Towards an arms trade treaty: establishing common international standards for the import, export and transfer of conventional arms.”(2) This resolution enabled the UK and like‐minded countries to assemble experts to assess the feasibility of formally launching an ATT negotiation process. Then, in 2009, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 64/48, entitled “The Arms Trade Treaty,” which established a schedule for pre‐negotiation meetings (known as Preparatory Committees, or PrepComs) resulting in a final Diplomatic Conference in July 2012.(3)

The goal of the ATT is to “to elaborate a legally binding instrument on the highest possible common international standards for the transfer of conventional arms.”(4) The scope is likely to include everything from helicopters to hand grenades, from tanks to target pistols and ammunition. It is hoped by humanitarians that a legally binding UN ATT championed by like‐minded states could be shaped to complement the merely politically‐binding 2001 UN PoA.

While all this treaty advocacy was going on, many of the same actors adopted a more discreet approach to binding international law for small arms and ammunition. Rather than just pursue their ambitious goals through a treaty out in the open, they also quietly started developing small arms control standards and customs. An example of this is the UN CASA (Coordinating Action on Small Arms) project, which is overseen by the UN’s Office of Disarmament Affairs.(5) UN CASA is euphemistically described as the “small arms coordination mechanism within the UN” to “frame the small arms issue in all its aspects, making use of development, crime, terrorism, human rights, gender, youth, health and humanitarian insights.”(6) In practice this organization is like a lawmaking committee or agency, but not nearly as accountable.

In 2008, CASA launched what they themselves described as “an ambitious initiative to develop a set of International Small Arms Control Standards (ISACS).”(7) UN CASA’s ISACS project includes eighteen mostly small and developing countries (none of them permanent security council members), fifteen international, regional and sub‐regional organizations, 33 humanitarian civil society groups, 23 other UN bodies, and just one Belgian firearms company, and one Italian national sporting arms and ammunition industry association.(8)

Ultimately, UN CASA’s ISACS initiative will eventually result in customary international law. Customary international law is the result of international administrative rule making which acquires the same weight as treaty law over time. States can be bound by customary international law regardless of whether the states have codified these laws domestically. Along with general principles of law and treaties, customary law is considered by the International Court of Justice, jurists, the United Nations, and its member states to be among the primary sources of international law.(9)

Truth be told, the UN’s PoA, the ATT, and CASA ISACS are predicated on false assumptions regarding small arms and ammunition. The two most important of which I will discuss here. Both of these assumptions are generally false in view of recent statistical studies and published scholarship.

The first assumption is that proliferation of small arms is a universal threat to human security, or, alternatively, that greater availability of small arms means more gun deaths in a given society. This is best quoted by the Geneva‐based Small Arms Survey (SAS), a special interest research group funded by various United Nations organizations, and other countries advocating stricter small arms controls.(10) The SAS officially states that the driving assumption behind all their research is the unqualified universal idea that “proliferation of small arms and light weapons represents a grave threat to human security.”(11) In fact, Nicholas Florquin, a senior researcher at SAS, started his talk during a two day seminar on Small Arms and Human Security in November 2011 with a stronger statement that, “proliferation of small arms causes problems” for humanity. (12)

Clearly, the small arms situation in some places may indeed be threatening to human security. But proliferation, i.e. the distribution of arms or expanding private ownership of arms, is not intrinsically a bad thing for everyone everywhere, especially in an ordered society. Proliferation, in fact, can be a force for good even in a disordered societal situation.

The American experience alone invalidates the global causative relationship between small arms proliferation and human insecurity. For example, trend data over the past nearly 20 years shows the US has been experiencing a phenomenal 35% decline in the number of gun deaths, even more in per‐capita terms.(13) This is part of a long term general trend in lower criminality. Over the same period firearms‐related suicides per 100,000 people declined by nearly 20%, the population grew over 20%, gun availability spiked (firearms sales boomed while statistically insignificant numbers of guns were bought back or otherwise destroyed), and, in 2011, indicators of national gun ownership rates increased to their highest level since 1993.(14,15) In other words, what we see in the US is the flipside of the assumption, that proliferation of small arms coincides with less gun violence. While this situation doesn’t necessarily mean more guns causes less gun violence, it does mean that the “more guns means more violence” assumption is simply not valid.

The French experience arming revolutionaries abroad invalidates the moral aspect of this first assumption, that proliferation is intrinsically bad. In fact, France alone has shown there can be a democratic and human rights upside of small arms proliferation. Have humanitarian campaigners forgotten that France armed liberty‐seeking American revolutionaries against colonial Britain? Are they denying that France also armed liberty‐seeking Libyan revolutionaries last year, and, ultimately, facilitated the demise of a regional dictator and notorious human rights abuser? These experiences prove even legally questionable state‐sponsored small arms proliferation to “insurgents” and “revolutionaries” can actually be a good thing for some societies and their local humanity.

The second assumption is that there is a plague of international illegal weapons trafficking threatening humanity everywhere. In fact, Rachel Stohl, the long‐time private consultant and insider working directly for Ambassador Moritán managing the ATT processes, has even published that “Without a doubt, it is the illegal arms trade and its various actors, agents, causes and consequences that capture our attention and motivate our action.”(16)

New research suggests the problem of illicit international trade in arms is not nearly as bad as first hypothesized over 10 years ago. Humanitarian campaigners’ evidence about the vast size, global scope, and cataclysmic impact of international illicit trafficking simply does not exist. Granted, it’s hard to quantify such illegal activity. Nontheless, the assertion that illicit international small arms trafficking is a major problem for the world has in fact been disproven over 10 years of progressively improved knowledge on the topic by academics and specialist researchers.(17)

To this day, however, the UN still claims on its Office of Disarmament Affairs website that international trafficking is a “worldwide scourge,” and that it “wreaks havoc everywhere.”(18) Campaigners, and their UN organizational sympathizers, must embrace the truth and acknowledge that the world is NOT actually suffering from a scourge of illegal international arms trafficking everywhere. At best, some failed or fragile states, conflict or post‐conflict regions may be suffering from illegal trafficking, but even this is of dubious importance ranked against other concerns like local diversion of small arms from government arsenals. Deaths and violence by small arms and light weapons are, on the whole, symptomatic of more local causes rooted within societies, and not cross‐border transfers.

The inconvenient truth today for humanitarian campaigners for international small arms controls is that for most countries around the globe, even for most developing or fragile states, a combination of deficient domestic regulation of legal firearms possession with theft, and loss or corrupt sale from official inventories is a more serious problem than illicit trafficking across borders.(19) The much touted scourge of illicit trade in small arms must be recognized, therefore, as hyperbolic humanitarian catastrophizing, or as we say in business, “marketing hype.”

In conclusion, while hyping of the size, scope, and impact of the illicit aspects of the arms trade was a de facto condition for first building consensus and momentum for the PoA, the ATT, and programs like CASA ISACS, continuing to do so presents serious reputational risk.(20) Continuing to assert that proliferation of small arms in society is intrinsically a bad thing for humanity presents serious reputational risk as well. Ultimately, such apparent dishonestly in the pursuit of otherwise admirable humanitarian goals raises questions about hidden agendas, institutional credibility, integrity, and organizational subject matter expertise. If the UN and humanitarian organizations really want to promote human security around the globe, honesty is still the best policy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeff Moran, a Principal at TSM Worldwide LLC, is a business consultant specializing in the international defense & security industry. He studies negotiations & policy‐making at the Executive Masters Program of the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. Previously Mr. Moran was a strategic marketing leader for a multi‐billion dollar unit of a public defense & aerospace company, a military diplomat, and a nationally ranked competitive rifle shooter. Jeff Moran has an MBA from Emory University’s Goizueta Business School and a BSFS degree from Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service

© 2012. Jeff Moran and TSM Worldwide LLC. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and republication are authorized when Jeff Moran and URL are referenced. http://tsmworldwide.com/dishonest‐humanitarianism/ DISHONEST HUMANITARIANISM? The invalid assumptions behind the United Nations small arms control initiatives.

END NOTE

1 http://www.poa‐iss.org/PoA/poahtml.aspx

2 http://daccess‐dds‐ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/499/77/PDF/N0649977.pdf

3 http://daccess‐dds‐ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N09/464/71/PDF/N0946471.pdf

4 Ibid.

5 http://www.poa‐iss.org/CASA/CASA.aspx, http://www.un‐casa.org

6 http://www.poa‐iss.org/CASA/CASA.aspx

7 http://www.un‐casa‐isacs.org/isacs/Welcome.html

8 http://www.un‐casa‐isacs.org/isacs/Partners.html

9 http://www.ll.georgetown.edu/intl/imc/imcothersourcesguide.html, http://www.mpepil.com/sample_article?id=/epil/entries/law‐9780199231690‐e1393&recno=29&, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Customary_international_law

10 Small Arms Survey, established in 1999, is supported by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, and by sustained contributions from the Governments of Canada, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The Survey is also grateful for past and current project support received from the Governments of Australia, Belgium, Denmark, France, New Zealand, Spain, and the United States, as well as from different United Nations agencies, programs, and institutes.

11 http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/about‐us/mission.html

12 November 4, 2011. This author was a note‐taker and participant in this seminar, which was hosted by the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

13 http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/homicide/tables/weaponstab.cfm, http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_us.html.

14 http://www.gallup.com/poll/150353/self‐reported‐gun‐ownership‐highest‐1993.aspx?version=print

15 http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_us.html

16 Rachel Stohl and Susan Grillot. The International Arms Trade. Polity Press: 2009. P. 93

17 Owen Greene and Nicholas Marsh, eds. Small Arms, Crime and Conflict: Global Governance and the Threat of Armed Violence. Routledge: 2012. P. 90.

18 http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs//2010/dc3247.doc.htm.

http://www.un.org/disarmament/convarms/SALW/

19 Owen Greene and Nicholas Marsh, eds. P. 91.

20 Anna Stavrianakis. Taking Aim At the Arms Trade: NGOs, global civil society, and the other world military order. Zed Publishing Ltd: 2010. P. 143‐4S